This past winter I had the opportunity to attend a workshop with Organization of American Historians distinguished lecturer, Dr. Lendol Calder. This is the first place where I came across the strategy called Book In An Hour. Since then I’ve tried to find additional internet resources on this strategy, but they appear to be few and far between. I know other people would find it useful, so I decided to write up the strategy and post it here on the blog. If you know of additional resources or ways to adapt this strategy, I would enjoy hearing from you.

What: The Book In An Hour strategy is a jigsaw activity for chapter books. While the strategy can take more than an hour depending on the reading and presentation method you choose.

Why: While many teachers view this activity as a time saver, I view it as a way to expose students to more literary and historical materials than I might have been able to do otherwise. There are many books that I would love my students to read, but I know that being able to do so is not always my reality. This strategy gives me an avenue to expose them to additional literature and other important historical works without taking much time away from the other aspects of my courses. It also provides opportunities for differentiation. This strategy can be adapted to introduce a book that students will be reading in-depth. Instead of jigsawing all of the chapters, use the same strategy with only a few selected chapters to create interest and engagement.

Procedures:

- Decide if you are going to divide students up into groups or jigsaw with individual students. If you are using groups, I recommend making them heterogeneous or creating them in a way that subtly facilitates differentiation. I also encourage you to give each student in the group a role (facilitator, recorder, reader, questioner, creative designer, whatever fits the needs of your adaptation of the strategy).

- Divide the book into sections. You can either break it down so each group/individual has approximately the same reading load (these sections can be randomly assigned) or differentiate and assign sections based on reading skills. Be sure each student has their assignment written down somewhere. You could write the chapter assignments for each group on large note cards or bookmarks, hand out a direction sheet that includes the assignments, have students write them down, etc .

- Hand out the reading sections to groups/individuals. Some teachers choose to take apart the actual books, rebinding them so students only have the section they are assigned.

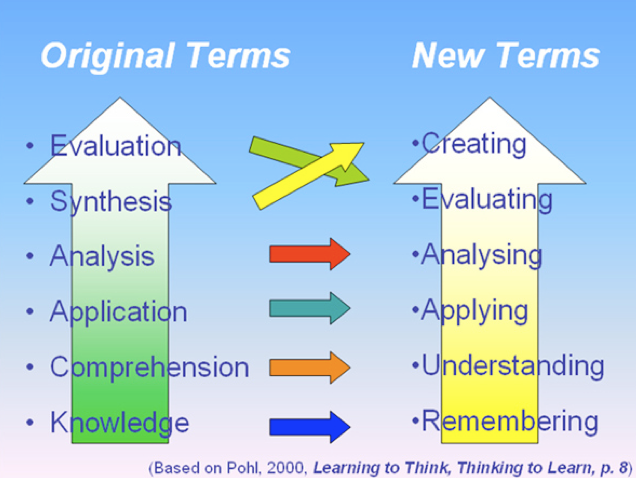

- Students then read their assigned sections. If you are using groups, it seems to be better to allow them to read their section together in class. There are several methods you can implement as students read to improve comprehension and to help them prepare to present their information to the rest of the class. If they are in a group, they may read together and complete the set of tasks you give them while doing so. They may also read individually, with set times to stop and complete the group tasks before reading more. The tasks that you can have students complete as they read include asking questions (since they only have part of the story…this is also a great opportunity to work with students on asking higher level questions), identifying plot, setting, characters, chronology of events, significant events, cause/effect, compare/contrast, documented evidence (in historical scholarship and other research readings), items related to a theme or focus question, presentation ideas, and anything else that fits your purpose. Students can record their findings on a teacher-created template, notebook paper, index cards, or anything that works for you. Lendol suggested using big paper, 12″ x 18″ or larger. The paper is placed in landscape position and the left side is folded in about ¼ of the of length of the paper. Below is a diagram of how he set it up for his students. Note: In the questions section, students can be directed to use a number of responses or prompts such as “I wonder if…”, make predictions, ask about missing prior events/knowledge, ask leveled questions (using a structure such as Bloom’s Taxonomy), etc.

The paper is folded to create the sections, and the front becomes a flap that folds over. - Have students create their presentation. You can give them a specific format, or leave the choice up to them. Options include (but certainly are not limited to): skits, posters, cartoons/comics, movies, Keynote or PowerPoint presentations (please not just slides to be read…students should present!), song playlist or soundtrack that highlights themes, events, characters, etc. You can incorporate technology and have students create a webpage, wiki, blog, Glog, Wordle, podcast, and more. The sky is the limit for ways the information can be brought together. Do whatever best fits your class and your purpose.

- Have students present their information, using your selected method, to the other students in the class. Be sure that there is a way for students to interact and get answers to their question. They need to see the whole picture when everything is done.

- It is a good idea to have a whole class conversation on the themes or focus question for the book. Direct the conversation to meet your needs and discuss how the book fits in to your overall unit plan. It is good to be sure students understand why this book was important enough to study. You can also have charts to be filled out as a class (poster style or on the white/chalkboard) that include topics such as historical events, themes, characters, plot, setting, timeline, cause/effect, compare/contrast, etc.

- You can let the final discussion or presentations be your method of assessment for the book, or you can have students complete a synthesis activity using numerous writing styles and prompts or other methods you find useful.

I suggest obtaining student feedback on Book In An Hour, especially the first few times you use it, so you may better tweak it to the learning needs of your students. This is an interesting strategy that has the potential to motivate students to read the entire book on their own. Again, if you have ideas for other adaptations, questions or other feedback, please feel free to comment. I’d love to hear how this works in your classroom.

Resources Consulted:

- Smith, Cyrus F., Jr. “Read a Book in an Hour: Variations”

- Daly, Lana “Read One Book in an Hour”

- A special thanks to Dr. Lendol Calder for introducing me to this strategy. Dr. Calder’s website on the practice of “Uncoverage” of history can be found here.